The potter’s wheel spins, a primordial dance of gravity and human touch. In studios from Jingdezhen to Faenza, an unspoken alchemy occurs—one where the whorls of a maker’s fingertips become inseparable from the clay they coax into being. This is not merely craft; it is a biological contract written in spirals.

Archaeologists have long studied ceramic fragments for clues about ancient trade routes or dietary habits. But Dr. Elara Voss’s recent monograph “Ceramic Dermatoglyphics” proposes something radical: that a potter’s unique fingerprint ridges can survive firing temperatures up to 1300°C, fusing with the vessel’s crystalline structure. Her team used reflectance transformation imaging on Song Dynasty sherds, revealing epidermal signatures preserved like prehistoric cave art.

Contemporary ceramicists report peculiar phenomena. When throwing exceptionally thin porcelain—walls barely 2mm thick—the clay seems to “remember” the maker’s touch long after trimming. Japanese master Hoshino Yūta describes it as “the clay stealing part of your soul”, noting how his students’ early works bear distinct pressure patterns that gradually harmonize with their teacher’s over years of apprenticeship.

This biomechanical symbiosis reaches its zenith in centripetal throwing, where the wheel’s rotation exceeds 300 RPM. At such velocities, the boundary between flesh and earth blurs. High-speed footage shows how fingerprints don’t simply imprint the surface—they generate microscopic turbulence in the clay particles, creating helical patterns that persist through bisque firing. These aren’t surface decorations, but volumetric signatures woven into the ceramic matrix itself.

Forensic ceramologist Dr. Marcus Wei made a startling discovery while analyzing Ming-era repair techniques. The “graft seams” where broken vessels were reassembled using fresh clay contain overlapping fingerprint evidence suggesting multiple artisans worked simultaneously—their hands moving in concert like a cellular membrane repairing itself. This challenges previous assumptions about solitary studio practices in imperial kilns.

The phenomenon has sparked ethical debates in conservation circles. When a 16th-century Italian albarello was laser-scanned at the Victoria & Albert Museum, researchers identified at least seven distinct fingerprint sets in its walls. Curator Isabella Conti argues these biological traces constitute “the artwork’s first layer of provenance”, while purists insist such human residue distracts from formal artistic analysis.

In Oaxaca’s pottery villages, the knowledge has always existed in folk form. Zapotec elders speak of “clay kinship”—how children’s early pinch pots naturally mirror their mother’s thumbprints long before formal training begins. Anthropologist Dr. Nia Khan recorded entire multi-generational fingerprint “dialects” in Blackware families, with certain ridge patterns recurring like grammatical structures in a visual language.

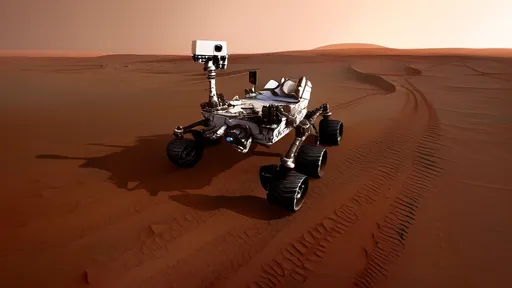

The implications extend beyond art history. Materials scientist Dr. Raj Patel’s team at MIT has developed a ceramic authentication protocol using atomic force microscopy to map fingerprint-induced nanostructures. Unlike brushstrokes or glazing techniques, these biological markers resist forgery because they result from unconscious neuromuscular interactions with specific rotational forces.

Perhaps most poetic is what happens when wheels stop. As the thrown form settles into its final shape, the last visible ridges aren’t from the potter’s hands—they’re the clay’s own “memory waves”, recording every hesitation and certainty in mineralized braille. In this silent exchange between earth and epidermis, we find proof that no vessel is ever truly anonymous.

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025

By /Aug 8, 2025